Tim Berne took a moment from his busy touring schedule to talk to New Music Circle about his ongoing project, Snakeoil. The group has just released You’ve Been Watching Me, their third album for ECM. The Guardian described Snakeoil as a group that ” ingeniously joins intricately multi-voiced music, lyricism, contemplation, and rugged avant-funk.”

Can you tell me about your current tour?

Yeah, we are playing about 15 cities in the States, as well as Europe and South America. Right now we are in the Midwest route of our tour, which includes Chicago, Detroit, Minneapolis, and St. Louis. I Believe our last visit to St. Louis was around 1997 with Bloodcount. Actually, we released a live cd of that concert.

What are your thoughts on touring and the current state of touring for you in the US?

This tour, audience-wise, has been way above average…really good turnouts. I would say lately it’s been better than usual. It’s always hard work, at least for me, because I always book the tours myself, and the transport is difficult because of the great distances. But as far as playing the States goes, I love doing it, and in terms of this tour in particular all the audiences have been really amazing and enthusiastic and fun. People always ask what the difference is between playing in the US and in Europe, and I would say the shows might be easier to get in Europe, but audiences are better here. For instance, our show the other night in Berkley: It was on a Sunday, and I was told to expect a slim audience…but it ended up being completely packed and people were excited about the music…

…the Snakeoil project has been continuing for awhile now, which probably helps a bit too…

Yeah! We’ve been together for a while now, and I feel like maybe we’ve built up some momentum in terms of folks latching onto the project. The thing about Snakeoil is that every time we go on tour the music changes pretty significantly, and that no one in the group is playing it safe. Even though we have tunes, the musicians rarely approach it the same way – (drummer) Ches Smith is playing a lot more vibes now, which changes the dynamic. Also, with Snakeoil, we rehearse more than most groups and have a level of commitment because of the consistency of recording. It helps that we’ve been working on a record about every year and touring every year…I think all of this keeps everyone motivated. Seeing the response we’ve had from the recordings and live sets makes us want to keep doing it…

Can you tell me about the recent Snakeoil release on ECM, You’ve Been Watching Me?

The recording process has been pretty similar to the last few, as David Torn, who recorded our last one, produced this one as well. The way David mixes sounds is really three-dimensional. He knows how to get every detail out of the music. But recording-wise, after spending lots of time preparing, we go to the studio and then it happens super quick…usually in one or two takes. This one we made in about a day. Not to compare, but this may be one of my favorite of the Snakeoil series so far. The whole collaboration with ECM has worked out really well.

Something new for this group is the addition of guitars…

I try to throw a new thing into each album and I really wanted to bring something new in without messing with the chemistry, so there’s guitar on this one by Ryan Ferriera. Ryan’s worked with Matt Mitchell (Snakeoil pianist) over the last few years, and when he started working with Snakeoil it really worked out.

What is the writing process like for this group?

When I’m focused I can write a bunch of music in a few weeks. Then it takes rehearsals and gigs to work it all out. But I really try to think about contrast, and exploiting all the combinations between the instruments…taking shape as duos, trios, quartets, between the five of us. I’m looking to create some drama, so it doesn’t sound one-dimensional, “oh here’s the solo…” – that sorta thing.

Tim Berne and Snakeoil will be performing at 7:30 PM on Friday, May 8, at The Stage at KDHX.

While known to many for his keen vinyl-mastering skills, honored by the hundreds of releases which now grace his name, Rashad Becker has created a music of his own that sounds quite unlike anything else. Becker’s sole 2013 release, Traditional Music of Notional Species Vol. 1 (PAN), is a foray into the realization of possibilities and “fictions” technically capable by live electronic means, and thus creates temporary, sonic environments that are uncanny and compelling.

How different is the approach to your live performances from your recorded output? Do you hope to create something different in a performance context?

Naturally recorded music follows different rules of narrative and tension than music that is performed live. It also bonds with people’s biographies in different ways, the usage is simply entirely different. Although my pieces are conceived in the studio, I usually play them live for a while before i sit down to record them. I know my own attention span is bigger when I play my pieces live so I always run into trouble when breaking them down for a recorded format, as I like short pieces…..and if there was no one keeping me from endlessly cropping, my pieces would probably all be under 2 minutes!

What were some formative music experiences for you growing up in Germany?

Well, I grew up with a lot of weird and peculiar music around me as it was Germany at the beginning of the 80s…there was quite a lot of surprise, weird humour, peculiar rhythms, colors, and progressions. Only a few of these groups had international recognition while the scene was huge in Germany. Besides that, the early days of British industrial culture were very intriguing to me, and of course punk and hardcore in it’s most dilletantic and least macho forms. Though I am not sure though how much actual influence my musical socialization has on the music I play today, I think non-musical and even non-sonic influences might be even stronger, social memory…to the day still I find the most overwhelming musical experiences rather in traditional music from Asia, Asia minor, Africa and South America.

Speaking generally, has Berlin been a good place for you to discover and make art? Is there anything specific about your environment that facilities or inspires you creatively?

Berlin has been a good and rich diaspora for anyone following a special interest in the past, with things changing from 2000 on. Berlin always had special conditions, the division being one of them, the lack of grip and supervision on the eastern part after the wall came down being another one. What set Berlin aside from Paris and London for example was that people would go there to actually live there and not just to be there for a while to tick a box in their curriculum. That made for a lot of social and cultural longevity, people properly conspiring over long terms and the places/clubs/galleries etc being real long term forums for a certain culture and a certain group of people. On top of that, you really did not need to move money around to be able to live there. My first flat in East Berlin was about $3.00 for rent a month, the second one a steep 400% increase to about $12.00…so you would just engage in commercial activities like labour every now and then when money ran out, so people had time for more important things than moving money around.

You’ve mentioned that your music is inspired by fiction…

I have always liked the writers of the era that was called ‘visionary poetry’ or ‘hermetic literature’ in German and has been referred to as ‘German Gothic’ in other languages. Also I am fond of the early 20th century German expressionists – but, more than actually being inspired by fiction, writing music is a compensation for my lack of endurance to follow up with my rather big ambition to write words….

With your interest in fiction and traditional musics and their instruments, on the flipside, I was wondering what electronic instruments offer to you …what are the challenges and what are the rewards of using them?

Synthesizers have a stronger fictional potential and expansion than natural instruments, they do not necessarily carry as much weight/history/patina as natural instruments do and hence allow for a more novelty language. Basically every sound you synthesize has the potential to bring the whole idiosyncrasy of an actual new instrument to the table. In that regard it is precious to me that my music is purely synthetic, as it gives me a lot of room to create my own kind of fiction. In analogy to animated movies, I was always puzzled why so much of their vocabulary is actually an emulation of non-animated movies in terms of cinematography etc and why so little examples beyond completely abstract and artistic movies actually elaborate on the potential and freedom the animated format provides. In that sense to me synthetic music provides a different potential for sonic and musical fiction than music written and arranged for natural instruments.

A percussionist, sound-artist and composer, Eli Keszler’s M.O. involves the dense and relentless movement of sound. His drumming approach is quick, with a vested interest in small, microtonal points of attack – little snippets of “bings” and “bangs” that go by quickly and aspire, in Eli’s words, to “create something that moves so fast that it is slow”.

On the other hand, his travel schedule is anything but slow, with recent performance collaborations involving the likes of David Grubbs (curated by none other than STL ex-pat, Paul C Ha), Tony Conrad and Joe McPhee.

Your performances involve not only drumming, but also include resonating piano string installations, graphic scores, prepared guitar, and compositions for large groups – though I was curious if you see yourself as primarily a percussionist?

It’s interesting, because I feel most comfortable playing the drums, but at this point I wouldn’t consider myself to be primarily a drummer. All along since I became interested in writing and putting together my own music and art, I saw the drums as a tool amongst many others.

What is it specifically that draws to to percussion?

I’ve been playing the drums since I was 7 and the same things draw me to the instrument now that did then: I like the duality between the simplicity and complexity of the instrument, there is no instrument more basic and which through this primal quality reveals its endless construction and nuance. Unlike other instruments that go through technological shifts, the drums fundamentally in role and function really haven’t.

Your music juxtaposes long-form and deeply resonant sounds against your drumming, which itself is moves rapidly and is almost microscopic in it’s detail. How do you view the intersections of these disparate sounds? As a listener, this juxtapose you create is the core of your music, and it has a heavy emotional quality to it all.

Thanks! I am definitely interested in the psychological aspects of music and perception and often times I feel like my drumming, art and music operate like my mind which tends to run very slow or very fast and at many directions at once – instead of trying to deny this aspect of my mind or for that matter the way of the world and nature at large I have tried to go with it, and explore this multiplicity. I became interested in music which deals with close tunings and slow unfolding resonances and structures and have needed to solve the problem of pairing the drums and achieving this effect, which is essentially staccato, with this attempt to create the illusion of sustain, while keeping everything acoustic and raw. Essentially I’m working from an impossible premise – to create something that moves so fast that it is slow.

You have collaborated with several other artists NMC has presented in the past few years, Keith Fullerton Whitman, Joe McPhee and Tony Conrad…

All of these people you mentioned are not only great musicians and artists but great people as well. Keith Fullerton Whitman and I have a long time friendship going back to Boston where I grew up – he is very analytical and sees music through the lens of his encyclopedic knowledge of records and electronic music. Tony Conrad is someone who I admire for his vision and ability to merge both music and visual art into something that delves into an internal dialogue with himself over his long career, as well as with political discourse and models of music and society at large — and Joe McPhee is one of the most powerful musicians I’ve ever played with… the harder you push him the stronger he gets, and it seems limitless.

Could you tell us a little about your recent collaboration with David Grubbs (of Gastr Del Sol) at MIT? While I I know you’ve worked with artists of varying mediums, this is the only context I’ve heard of you working with poetry and language.

The project at MIT List Center which is up till the beginning of November was the first time for many things. I’ve never dealt with text or language in any projects in fact, though it’s something I’ve become increasingly interested in finding my relationship to. David contributed this very interesting long form poem which was chopped into small fragments and drawn on corners of the gallery. I built and designed 7 modular boxes which housed over 100 mechanical devices and small transducers, which were projecting fragments of David Grubbs text through acoustic objects – which the legibility of were mangled by these materials.

Your recent releases have been on the Berlin-based label, PAN, a label which produces visually stunning record sleeves and has an amazingly diverse roster that includes dance artists like Heatsick and Lee Gamble, as well as avant-garde pioneers like Evan Parker and Trevor Wishart…

I love PAN and what (label head) Bill Kouligas creates by curating such a span of musical styles and approaches under the umbrella of the label, and his awareness of how the visual components and design can add something important to the experience of putting on a CD or LP. I appreciate Bill’s vision and his ability to think critically about what it means to run a label today with no nostalgia or romanticism. He really pushes everyone the label to produce in a way that’s true to us, which is a very rare thing.

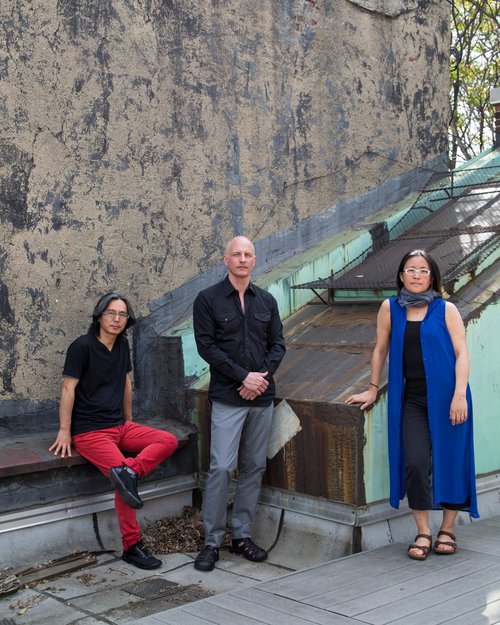

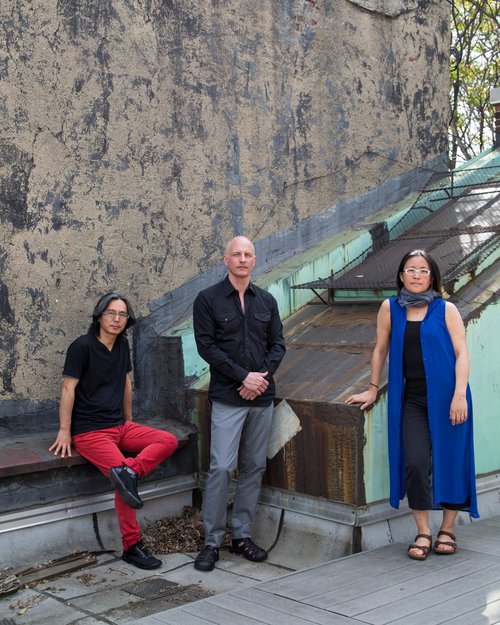

We recently asked guitarist Mary Halvorson a few questions about Thumbscrew and her own musical background and approach. Be sure to catch Mary with Thumbscrew this Friday September 12th at Joe’s Cafe!

How did Thumbscrew come to form? My understanding is you’ve been playing with Tomas for awhile now…

Mary Halvorson: Thumbscrew’s beginning was an accident of sorts. Tomas and I have been playing together for 10 years now, and one of the many bands we play in together is Taylor Ho Bynum’s Sextet. A few years ago, Michael Formanek was subbing in Taylor’s band for a performance in New York, and the three of us (Michael, Tomas and myself) really hit it off musically as a rhythm section. We immediately talked about doing more playing as a trio. When we got together a few months later, we each wrote a couple pieces of music specifically for the new trio, and Thumbscrew took shape pretty organically from there.

Could you maybe talk a little about the qualities of both Tomas’ and Michael’s playing?

MH: For me it’s a real pleasure to play with both Michael and Tomas. Michael has been one of my favorite bass players ever since I was in college and discovered his playing through Tim Berne’s Bloodcount. I am also a huge fan of Michael’s records as a leader and numerous other projects he’s a part of. Thumbscrew was my first real opportunity to work closely with him, and it’s been quite an amazing experience. Tomas and I have been collaborating since 2004, in many different projects, from Matana Roberts to Mike Reed to Taylor Ho Bynum. I have always felt a strong musical connection with Tomas and have taken a lot of inspiration from his performing, composing and musical thinking, particularly as a part of his quintet, The Hook Up. Over the years I have enjoyed developing a strong musical rapport with him, now taking a new form in Thumbscrew.

Your last visit to St. Louis saw you playing in Taylor Ho Bynum’s Sextet (an incredible and memorable show!). What I noticed in Taylor’s writing approach was how he allowed vast amounts of compositional space for each musician’s voice, or character, to come through – even when there are six of you playing together in really tight musical sequences there still is a feeling it can go in an opposite direction at any moment. Could you share any insights into the process that musician/composers like Taylor and Anthony Braxton use for composing in these larger groups?

MH: Taylor has set up a really interesting musical system for his sextet. The latest piece of music he composed is basically a modular suite. There are six compositions, but the order in which the compositions happen is left partially open to the musicians in the band, through a road map format. Band members can cue certain pieces in at certain times, and together those pieces function as one long continuous piece. The same composition might happen twice in a set, or might not happen at all. It’s interesting because the pieces are open enough that they can take on a really different form each time. And it’s a fun challenge to try to shape the pieces differently, to improvise endings, beginnings, and transitions. There is always a strong element of the unexpected.

Anthony Braxton’s larger ensembles have a similar yet distinct type of freedom. In many of his bands, musicians can cue in other musicians and even bring in entirely new compositions, improvised sections or structured improvisations in the midst of another composition. Sometimes there are section leaders within a larger ensemble, and section leaders can cue smaller sub-groups. The compositions that are created, like Taylor’s, are dynamic, based on larger structural systems, and are never performed the same way twice.

In the works you write/lead in (i.e. Mary Halvorson Quintet), where do you start with the composition? From guitar? Or do the ideas begin in a more abstract and conceptual manner?

MH: Normally I start a composition simply by improvising on guitar, until I come up with some sort of a small fragment or an idea that I can use as a seed for a composition. Getting that initial idea can take a long time, but once I get it I write pretty quickly and improvisationally; I elaborate on the fragment or idea and keep adding to it and changing it until it starts to take shape. I rarely have an overarching structural idea beforehand, so the compositions might go in any direction and often wind up in an entirely different place than they started.

When listening to your playing, not only does the listener notice the complexities and phrasings of your playing, but also the tonal sound itself as a defining part of your music. Was there a process that lead you this particular sound and setup we hear in your guitar-work?

MH: I’ve always enjoyed the acoustic sound of a guitar; the imperfections of the wood, buzzes, attack of the pick, etc. For that reason, I was drawn to a big archtop guitar, because even if it’s amplified, you can still hear a lot of the natural sound of the instrument. As far as an amplified tone, I’ve never liked reverb, and I tend to go for a sound that is clean and warm, and emulates the natural sound of the instrument, as a starting point. From there, I sometimes like to add effects (delay, pitch bending, distortion, tremolo). But I’ve always thought of those effects as an ornamentation of sorts to a more natural, clean sound.

Have there been any notable shows or music you’ve caught recently that you’d like to share?

MH: This July I did a solo guitar tour opening up for Buzz Osborne of the Melvins, who was doing a solo acoustic tour to support his new album, This Machine Kills Artists. I’ve always loved the Melvins, and hearing Buzz in a solo context was mindblowing. With the simple, stripped-down format of acoustic guitar and vocals, he performed an extraordinarily powerful and uncompromising set without losing an ounce of the intensity and energy of a full band. I had the privilege of listening to it for seven nights straight and never once grew tired of it.